The greatest risk to your sight isn’t a disease, but the false sense of security created by your own brain, which actively hides evidence of damage.

- Vision loss from glaucoma often begins silently in the periphery, with your brain creating a seamless, but fake, visual world to compensate.

- “Normal” eye pressure is not a guarantee of safety; a significant portion of glaucoma damage occurs due to poor blood flow to the optic nerve, a factor standard tests can miss.

Recommendation: Shift from passive waiting to active investigation. Use the timeline and family history questions in this guide to build a case for early, targeted professional screening.

You feel perfectly healthy. Your vision seems sharp, you pass the driver’s license eye chart with ease, and life proceeds without any noticeable visual disruption. Yet, a nagging thought persists, perhaps fueled by a grandmother who “lost her sight” or an uncle who uses daily eye drops. This is the paradox of silent, sight-threatening diseases like glaucoma: they are masters of camouflage. The conventional wisdom to “get regular eye exams” is sound, but it’s dangerously incomplete. It fosters a passive mindset in a battle that demands an active, investigative approach.

The core problem is that we trust our perception. We assume that if something were wrong with our eyes, we would see it. This is a fundamental, and potentially tragic, misunderstanding of how vision works. Your eyes are merely the cameras; it is your brain that is the editor, and it is ruthlessly efficient at concealing errors. It will “fill in” missing information, stitch together a coherent picture from damaged signals, and maintain an illusion of normalcy while the underlying hardware—the optic nerve—is progressively failing.

But what if the key wasn’t waiting for a symptom to appear, but learning how to unmask the deception? This guide is not a simple list of risk factors. It is an investigative framework. We will dissect the mechanisms of visual deception, differentiate between benign signals and true emergencies, and provide you with a concrete timeline and a set of forensic questions to investigate your own genetic risk. The goal is to transform you from a passive patient-in-waiting into a proactive health detective, armed with the knowledge to demand the right tests at the right time.

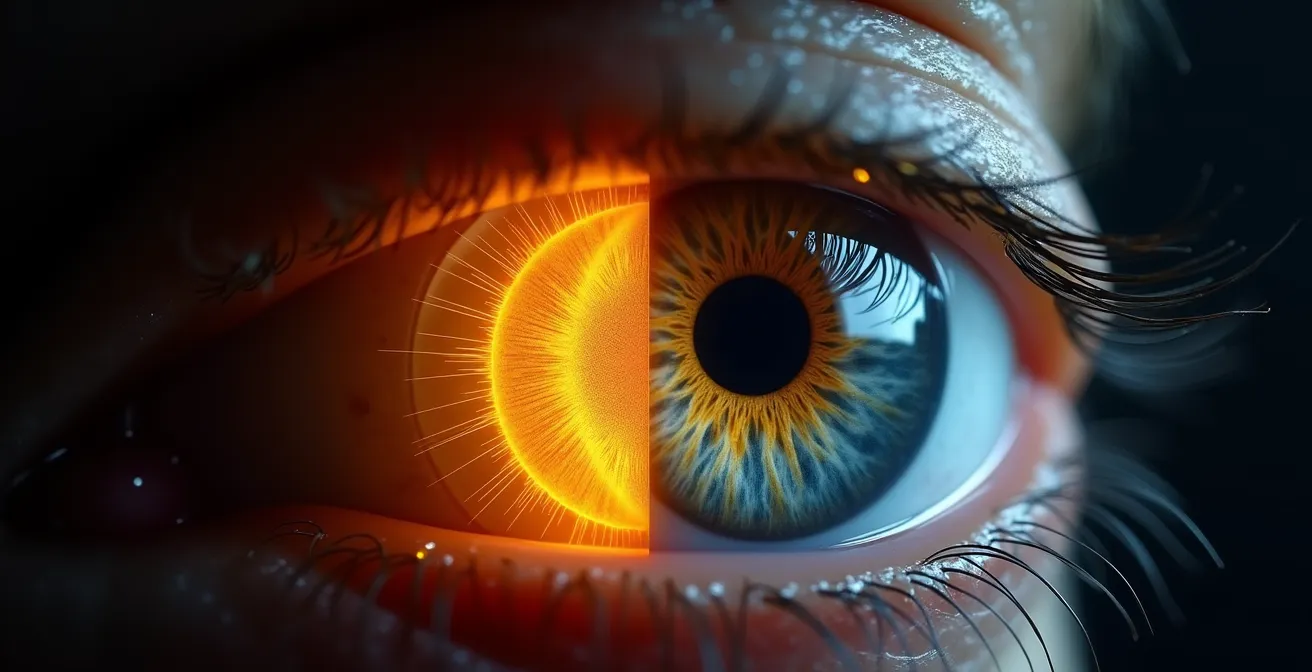

For those who prefer a visual format, the following animation provides an excellent overview of how professionals detect glaucoma during a dilated eye exam, highlighting the very structures we will be discussing.

To help you navigate this investigation, this article is structured to build your understanding step-by-step. We will move from the internal deceptions of your own brain to the external clues you can gather from your family and your own health profile, providing you with a complete toolkit for preventative vigilance.

Summary: Investigating the Silent Threats to Your Vision

- Why Your Brain “Fills In” the Gaps Caused by Retinal Damage?

- How to Use an Amsler Grid on Your Fridge to Check for Distortion?

- Sudden Flashes or Slow Fade: Which Symptom Demands 911?

- The Genetic Risk: Why You Need Early Screening if Grandma Went Blind

- When to Start Annual Scans: The Timeline for High Myopes

- Why You Can Lose Vision Even With “Normal” Eye Pressure?

- The Danger of “Ripe” Cataracts: Why Waiting Increases Surgical Complications

- Why Tears and Detachments Hide in the Far Periphery?

Why Your Brain “Fills In” the Gaps Caused by Retinal Damage?

The single most dangerous characteristic of chronic glaucoma is its silence, a silence actively manufactured by your brain. When cells in the optic nerve are damaged, they create blind spots, or “scotomas,” in your visual field. You might expect to see black patches or holes, but you almost never do. Instead, your brain engages in a remarkable process called “perceptual filling-in.” It takes the visual information from the surrounding healthy retina and “pastes” it over the blind spot, creating a seamless, plausible, but ultimately fake, visual experience. You don’t see a hole because your brain has edited it out of the final picture.

This isn’t a passive process; it’s an active deception. A 2021 study on the Riddoch Phenomenon demonstrated this paradox: some glaucoma patients could detect a moving object passing through their blind spot but were completely unaware of a static object in the same location. The brain’s motion-detecting pathways remained partially active while its form-recognition pathways were not, highlighting the complex and unreliable nature of self-perception. This is why you can have 20/20 vision on a standard eye chart, which tests only your sharp, central vision, while having lost a significant amount of your peripheral field. Studies show the brain can compensate for up to 40% of peripheral vision loss before you become consciously aware of a problem.

This neurological camouflage is why relying on self-perceived symptoms for chronic glaucoma is a flawed strategy. The absence of symptoms is not evidence of health; it’s often evidence of your brain’s incredible ability to adapt and deceive. The only reliable way to catch this silent destruction is through professional testing that maps your entire visual field, one eye at a time, to bypass the brain’s compensatory tricks.

How to Use an Amsler Grid on Your Fridge to Check for Distortion?

Given the brain’s ability to hide peripheral loss, you might look for tools to monitor your central vision. The most common is the Amsler grid, a simple pattern of straight lines with a central dot. The test is straightforward: cover one eye, stare at the central dot from about 12-15 inches away, and notice if any lines appear wavy, distorted, or are missing. Attaching one to your refrigerator for a daily check seems like a proactive, simple step to monitor your eye health.

This daily check can be a valuable habit, especially for detecting issues related to the macula, the center of your retina. However, placing your trust solely in the Amsler grid for glaucoma detection creates a dangerous false sense of security. It is a tool designed for the wrong problem.

As the table below clarifies, the Amsler grid is a specialist. It is excellent at detecting distortion in the central 10-20 degrees of your vision, which is characteristic of diseases like macular degeneration. Glaucoma, in its most common form, is a disease of the periphery. It begins its silent assault on the outer edges of your vision, an area the Amsler grid is completely blind to. You could have a perfectly normal Amsler grid test every day while significant, irreversible glaucomatous damage is occurring in your peripheral visual field.

| Test Type | What It Detects | Limitation | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amsler Grid | Central 10-20° distortion | Misses peripheral glaucoma damage | Macular degeneration, diabetic maculopathy |

| Confrontation Field Test | Gross peripheral defects | Not diagnostic, very crude | Educational awareness only |

| Professional Perimetry | Detailed field mapping | Requires clinic visit | Glaucoma diagnosis and monitoring |

Sudden Flashes or Slow Fade: Which Symptom Demands 911?

While chronic glaucoma is defined by its gradual, painless progression, not all sight-threatening conditions are so subtle. The eye can also produce dramatic, acute symptoms that serve as a critical alarm. The challenge for a health detective is to distinguish between the “background noise” of normal aging (like occasional, slow-moving floaters) and a true five-alarm fire. Knowing how to triage these symptoms can be the difference between preserving sight and permanent loss. A sudden “shower” of new floaters, especially when accompanied by flashes of light like a lightning storm inside your eye, is not to be ignored. This combination is a classic sign of a retinal tear or detachment, a medical emergency.

The flashes are caused by the vitreous gel, which fills the eye, pulling on the retina. The “shower” of floaters is often tiny specks of blood or retinal cells released into the eye. Another critical emergency signal is the appearance of a dark curtain or shadow moving across your field of vision. This indicates an active retinal detachment, where the light-sensitive tissue has pulled away from the back of the eye. For a retinal detachment, immediate treatment within 24-48 hours is paramount to prevent permanent blindness in the affected area.

Conversely, symptoms like gradually worsening night vision or a slow, painless loss of peripheral vision over months or years are characteristic of chronic glaucoma or developing cataracts. These require an appointment with your ophthalmologist but are not typically 911-level emergencies. The key is to understand the language of your symptoms: sudden, dramatic, and new events demand immediate action, while gradual changes demand prompt, but scheduled, investigation.

- CALL 911/ER NOW: Sudden shower of floaters with lightning flashes (retinal tear risk).

- CALL 911/ER NOW: A dark curtain or shadow moving across your vision (active retinal detachment).

- URGENT (24-48 hours): Sudden severe eye pain with halos around lights (acute angle-closure glaucoma).

- ROUTINE APPOINTMENT: Gradual, painless peripheral vision loss over months (chronic glaucoma).

- ROUTINE APPOINTMENT: Increasing difficulty with night vision or glare (cataract progression).

The Genetic Risk: Why You Need Early Screening if Grandma Went Blind

Of all the risk factors for glaucoma, family history is the most significant and the most frequently misunderstood. It’s not enough to know that a relative “went blind” or had “eye problems.” Acting as a health detective requires a more forensic approach to your genetic inheritance. Having a first-degree relative (a parent or sibling) with glaucoma means your own family history increases your glaucoma risk by 4 to 9 times compared to someone with no family history. This single factor can move you from a low-risk to a high-risk category overnight, mandating earlier and more frequent screening.

The problem is that family health histories are often vague. “Grandma went blind” could mean she had untreated cataracts, severe macular degeneration, or diabetic retinopathy—conditions with entirely different genetic implications than glaucoma. Your mission is to gather specific intelligence. When speaking with relatives, you need to ask targeted questions that go beyond the general and uncover the specifics of their diagnosis and treatment. Knowing the type of glaucoma (e.g., open-angle vs. angle-closure) and the age of diagnosis is critical information for your own ophthalmologist.

This isn’t about being nosy; it’s about collecting the data necessary to protect your own sight. A well-documented family history is one of the most powerful tools you can bring to your eye exam. It provides your doctor with a roadmap of your potential genetic vulnerabilities and justifies initiating screening protocols, such as baseline visual field testing and optic nerve imaging, years or even decades earlier than standard guidelines might suggest.

Your Family Health Detective Checklist: Key Questions to Ask

- Ask relatives: Was your vision loss gradual and painless, or was it sudden and painful?

- Document their treatment: Did you need to use eye drops every day specifically for “eye pressure”?

- Clarify the diagnosis: Did the doctor ever use the term “glaucoma,” and if so, what type (e.g., open-angle, narrow-angle)?

- Record procedures: Did you ever need laser treatment (SLT, LPI) or incisional surgery (a trabeculectomy or shunt) for your eyes?

- Note the timeline: At what age were you first diagnosed with the condition?

When to Start Annual Scans: The Timeline for High Myopes

Beyond genetics, one of the strongest and most overlooked anatomical risk factors for glaucoma is high myopia, or nearsightedness. People with high myopia (typically requiring a prescription of -6.0 diopters or stronger) have physically longer eyeballs. This elongation stretches and thins the optic nerve head and the surrounding retinal tissue, making them more susceptible to glaucomatous damage, even at normal eye pressures. This is an anatomical risk that cannot be ignored.

A common and dangerous misconception is that laser vision correction procedures like LASIK eliminate this risk. This is false. As the American Academy of Ophthalmology warns, these procedures reshape the cornea to correct focus but do nothing to change the internal length of the eye.

Laser vision correction like LASIK corrects focus but does not change the eye’s internal anatomical length or reduce glaucoma risk. High myopes remain high-risk regardless of refractive surgery.

– American Academy of Ophthalmology, Myopia and Glaucoma Risk Guidelines

Because of this inherent structural vulnerability, the screening timeline for high myopes must be more aggressive. While a person with no risk factors might start baseline glaucoma screening at age 40, a high myope should begin much earlier. The following table provides a risk-stratified approach, demonstrating how screening frequency should increase with the level of myopia and the presence of other risk factors like a family history of glaucoma.

| Myopia Level | Baseline Exam Age | Follow-up Frequency | Additional Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (-1 to -3D) | 40 years | Every 2 years | Annual if family history |

| Moderate (-3 to -6D) | 35 years | Every 1-2 years | Annual with OCT |

| High (>-6D) | 30 years | Annual | Include retinal periphery exam |

| High + Family History | Late 20s | Annual | Consider genetic counseling |

Why You Can Lose Vision Even With “Normal” Eye Pressure?

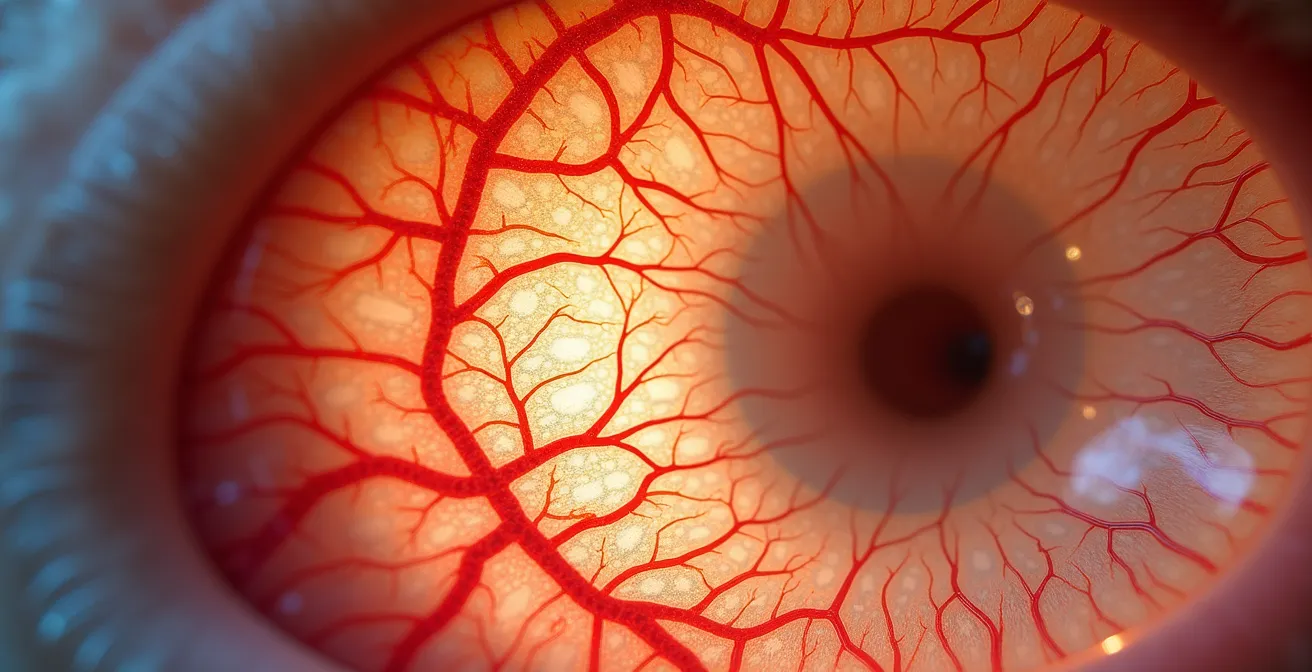

For decades, glaucoma was almost synonymous with high intraocular pressure (IOP). The “puff test” (non-contact tonometry) became the public face of glaucoma screening. While high IOP is indeed a major risk factor, an over-reliance on this single metric has led to a critical blind spot: Normal-Tension Glaucoma (NTG). In NTG, classic glaucomatous optic nerve damage and irreversible vision loss occur despite eye pressures that are consistently within the statistically “normal” range. This condition underscores a crucial shift in understanding glaucoma: it is not just a disease of pressure, but a disease of the optic nerve’s vulnerability.

The leading theory behind NTG points to vascular culpability. The optic nerve is a dense bundle of over a million nerve fibers, and it requires a rich, stable blood supply to function. For some individuals, the problem isn’t that the pressure in the eye is too high, but that the blood flow to the nerve is too low. This can be caused by systemic conditions like low blood pressure (hypotension), especially significant dips in blood pressure that occur overnight during sleep. This nocturnal hypotension can starve the optic nerve of oxygen and nutrients, leading to progressive damage.

Evidence for this vascular theory is growing. A 2024 study on NTG patients found that 43% had microvasculature dropout in the choroid (the layer of blood vessels behind the retina) associated with nighttime blood pressure dips. Patients with these nocturnal dips showed significantly more optic nerve damage, confirming that what happens in your circulatory system while you sleep can have a profound impact on your vision. This is why a single IOP reading during a daytime appointment can provide a false sense of security. A comprehensive investigation must also consider vascular risk factors.

Key Takeaways

- Your brain’s “filling-in” mechanism can hide up to 40% of peripheral vision loss, making self-monitoring for glaucoma unreliable.

- Sudden flashes and floaters or a dark “curtain” are emergencies requiring immediate ER attention; gradual changes require a routine appointment.

- A family history of glaucoma increases your risk 4 to 9 times; actively investigate the specific diagnosis, treatment, and age of onset in relatives.

The Danger of “Ripe” Cataracts: Why Waiting Increases Surgical Complications

Cataracts, the clouding of the eye’s natural lens, are often seen as a separate and less urgent issue than glaucoma. Many people adopt a “wait and see” approach, delaying surgery until their vision is significantly impaired. However, from an investigative standpoint, a dense, “ripe” cataract is not just an obstacle to your vision; it’s a major obstacle to diagnosis. It creates a critical blind spot for your ophthalmologist, preventing them from properly examining the health of your optic nerve and retina.

As cataract specialist Dr. Leonard K. Seibold explains, the surgery becomes about more than just improving the patient’s sight.

A dense, ‘ripe’ cataract acts like a curtain, making it impossible for the ophthalmologist to examine the retina and optic nerve. The surgery becomes not just about helping the patient see out, but crucially allowing the doctor to see in.

– Dr. Leonard K. Seibold, Cataract Surgery Timing Guidelines

Waiting too long doesn’t just delay diagnosis; it significantly increases the risks of the surgery itself. A hyper-mature cataract becomes harder and more brittle. This increases the amount of ultrasound energy (phacoemulsification) needed to break it up, which can cause collateral damage to the delicate corneal cells. Furthermore, the zonules—tiny ligaments that hold the lens in place—can become weak and brittle, risking a break during surgery. In some cases, a swollen cataract can even physically block the eye’s drainage angle, causing a spike in eye pressure and a secondary form of glaucoma known as phacomorphic glaucoma.

Waiting for a cataract to be “ripe” is an outdated and dangerous concept. Modern cataract surgery is safer and more effective when performed on less dense cataracts. Delaying the procedure not only prolongs your poor vision but can actively mask underlying diseases and complicate their eventual treatment.

Why Tears and Detachments Hide in the Far Periphery?

The final piece of the investigative puzzle lies in understanding the eye’s anatomy. The retina is not a uniform sheet; its structure and function vary dramatically from the center to the edge. The far periphery of the retina is thinner and more fragile than the robust central macula. It is in this remote, structurally vulnerable territory that most retinal tears and subsequent detachments originate. This location is a primary reason why these critical events can begin with such subtle symptoms.

A small tear in the far superior (top) periphery might initially produce no symptoms at all. As fluid seeps through the tear and begins to lift the retina, gravity takes over. This causes a “curtain” or shadow to appear in the opposite, inferior (bottom) part of your visual field. This topographical opposition is a key diagnostic clue for clinicians, but for the patient, it can be confusing. The initial event is silent, and the first symptom appears far from the actual site of injury. Furthermore, clinical analysis has shown that peripheral retinal tears can be ten times larger than central macular holes yet produce minimal symptoms initially.

This vulnerability is often initiated by a common, age-related event called a Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD), where the eye’s vitreous gel shrinks and pulls away from the retina. While PVD is a normal part of aging for most, for some, the gel is too adherent and pulls hard enough to tear the retina. It is estimated that up to 15% of symptomatic PVDs result in a retinal tear that requires urgent laser treatment to prevent a full-scale detachment. Because these tears hide in the periphery, any new onset of flashes or floaters must be taken seriously as a potential signal from this hidden, vulnerable zone.

The evidence is clear: protecting your vision is not a passive activity. It requires an investigative mindset, a deep understanding of your personal and genetic risk factors, and a partnership with an ophthalmologist to look beyond the obvious. Waiting for a clear symptom is often waiting too long. To put these principles into action, the next logical step is to schedule a comprehensive, dilated eye examination to establish a baseline and discuss your specific risk profile with a professional.