Contrary to popular belief, rinsing your contact lens case is not enough; it rapidly becomes a primary vector for infection due to invisible biofilm formation.

- Micro-scratches on the plastic surface create havens for bacteria that even vigorous rinsing cannot remove.

- Using tap water, even once, introduces dangerous microorganisms like Acanthamoeba, which are resistant to standard disinfection.

Recommendation: Replace your case every three months without fail, as this is the statistically supported timeframe to minimize the risk of a serious, sight-threatening eye infection.

If you’re a contact lens wearer, you have a daily routine. But a critical component of that routine is often neglected: the contact lens case. Many users, perhaps like you, have been using the same case for six months or more, believing a quick rinse is sufficient to keep it clean. The common advice is to replace it “regularly,” a vague term that fails to convey the urgency. This complacency is a significant, statistically measurable risk to your eye health.

The assumption that a visually clean case is a sterile case is fundamentally flawed. We tend to focus on lens care, overlooking the container that houses them for hours. But what if the true danger wasn’t the lens itself, but the microscopic environment of its case? The data is clear: the plastic of your case is an ideal breeding ground for resilient bacterial colonies, known as biofilms, that are impervious to simple cleaning.

This article moves beyond generic advice. Guided by a statistical and microbiological perspective, we will dissect the evidence. We will demonstrate why your case is a contamination vector, explain the non-negotiable science behind the three-month replacement rule, and provide the data-driven protocols to protect your vision. We will explore the properties of the plastic, the right and wrong ways to clean and dry your case, and what to do in specific situations to maintain absolute hygiene.

This guide provides an evidence-based framework for contact lens case hygiene. Below, you will find a detailed breakdown of the critical factors, from the microbiology of plastic surfaces to practical recycling advice, all designed to answer the central question of safe replacement frequency.

Contents: The Statistical Case for Lens Case Hygiene

- Why Plastic Cases Harbor Bacteria Even After Rinsing?

- How to Position Your Case to Air-Dry and Prevent Mold?

- Flat Case or Barrel Case: Which Uses Less Solution?

- The Chemical Residue Risk of Washing Lens Cases in the Dishwasher

- Problem & Solution: Keeping Your Case Sterile While Camping

- Why Rinsing Cases With Tap Water Risks Acanthamoeba Infection?

- Why You Must Discard Your Lenses Immediately Upon Seeing Redness?

- How to Recycle Daily Contact Lenses and Blister Packs Correctly?

Why Plastic Cases Harbor Bacteria Even After Rinsing?

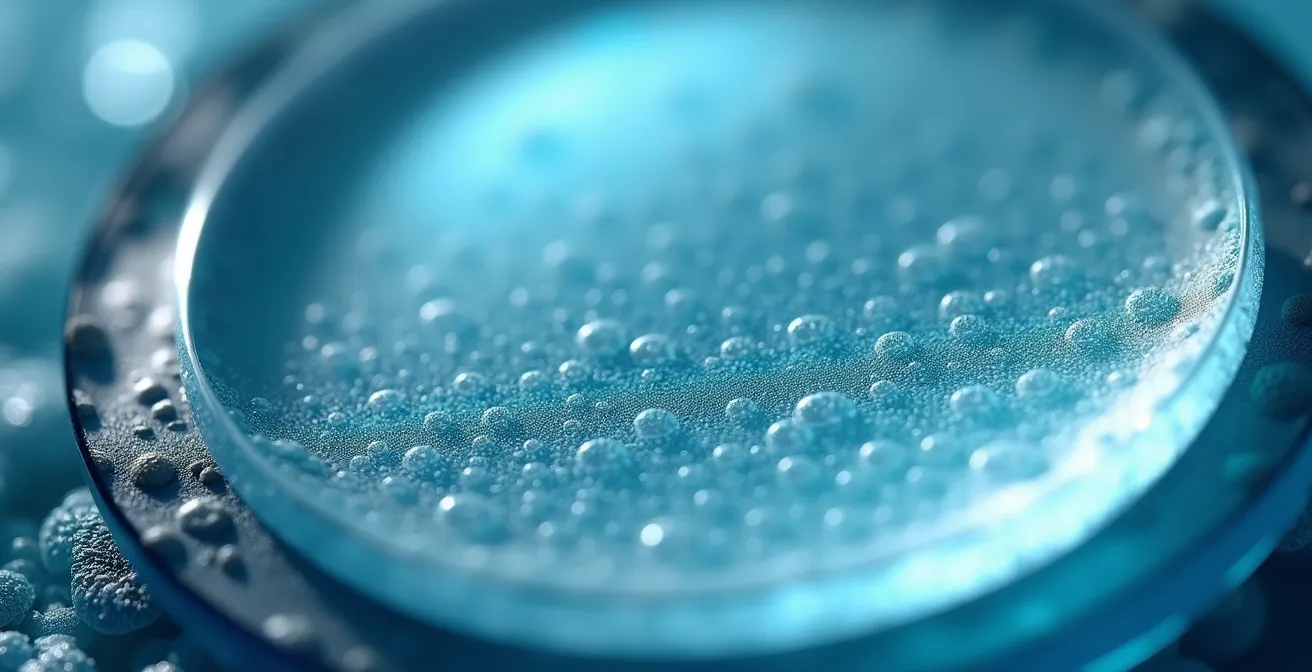

The fundamental problem with long-term case use lies at the microscopic level. The plastic, typically polypropylene, seems smooth to the naked eye. However, with repeated use, cleaning, and even the simple act of screwing the cap on, its surface develops a network of micro-abrasion havens. These tiny scratches and grooves are the perfect anchor points for bacteria to initiate colonization. Once attached, these microorganisms secrete a sticky, protective substance, forming a structured community known as a biofilm matrix. This is not just a random collection of germs; it is a fortress.

This biofilm is highly resistant to both chemical disinfectants in your solution and the physical force of a simple rinse. The protective matrix shields the bacteria within, making them up to 1,000 times more resistant than their free-floating counterparts. The evidence is stark: research shows bacterial biofilm was present in 85% of cases collected from patients suffering from microbial keratitis, a severe eye infection. Rinsing may wash away loose debris, but it does little to dislodge this entrenched microbial city.

As this image illustrates, the surface is far from perfect. Each scratch is a potential sanctuary for pathogens. Every time you place your lens in the case, it is bathed in this environment, increasing the microbial load transferred directly to your eye. This is why, from a statistical standpoint, the age of the case is directly correlated with infection risk. It’s not about visible dirt; it’s about the invisible, fortified biofilm that develops over time.

How to Position Your Case to Air-Dry and Prevent Mold?

Moisture is the catalyst for microbial growth. A damp contact lens case is a thriving ecosystem for bacteria and mold. Therefore, a rigorous drying protocol is as crucial as the cleaning process itself. The goal is to create a hygienic dry-zone where pathogens cannot multiply. Storing a wet case, especially in a humid environment like a bathroom, is a significant compliance failure. Bathrooms are notoriously high in airborne contaminants; research found that most contaminated cases, 72% showed mixed bacterial contaminants, are often linked to improper, damp storage in such areas.

The correct procedure involves more than just leaving the case open. It requires mechanical cleaning to disrupt biofilm formation before it can become established, followed by a thorough drying method. The objective is to remove both the biofilm and the moisture it needs to survive. The following plan outlines the evidence-based daily care routine that significantly reduces the microbial load in your case.

Your Action Plan: Optimal Lens Case Drying Technique

- Rinse the case thoroughly with fresh multipurpose solution immediately after removing your lenses.

- Rub the case interior and cap threads with clean fingers for at least 5 seconds to mechanically dislodge early-stage biofilm.

- Rinse again with fresh solution to wash away all dislodged debris and microorganisms.

- Wipe the case interior and caps dry with a clean, lint-free tissue to remove the bulk of the remaining moisture.

- Place the case and its caps face-down on a clean tissue in a low-humidity area to allow them to air-dry completely.

Placing the case and caps face-down is a critical step. It prevents airborne dust and contaminants from settling inside the wells while allowing air to circulate and evaporate any residual moisture. This daily discipline is your first line of defense against the colonization of your case between replacements.

Flat Case or Barrel Case: Which Uses Less Solution?

The design of your contact lens case is not merely aesthetic; it has a direct impact on disinfection efficacy and solution consumption. The two primary designs are the traditional flat case and the vertical barrel case. Choosing between them often depends on the type of disinfecting solution you use, particularly whether it’s a multipurpose solution or a hydrogen peroxide-based system.

Barrel cases are specifically designed for hydrogen peroxide solutions. These systems require a special catalytic disc, usually built into the barrel case assembly, to neutralize the peroxide into saline over a period of several hours. The vertical suspension of the lenses in the basket ensures they are fully immersed for 360-degree disinfection. Flat cases, on the other hand, are the standard for multipurpose solutions. They use less solution per cleaning cycle but present a higher risk of biofilm formation in corners and edges if not cleaned properly.

The following table provides a statistical and functional comparison between the two case types, highlighting their differences in solution volume, cleaning mechanism, and associated risks.

| Feature | Flat Case | Barrel Case |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Volume | 3-4ml per well | 10-12ml total |

| Lens Submersion | Horizontal placement | Vertical suspension |

| Best For | Multipurpose solutions | Hydrogen peroxide systems |

| Cleaning Efficacy | Standard disinfection | Enhanced with catalytic disc |

| Biofilm Risk | Higher in corners/edges | Lower with complete immersion |

From a volume perspective, a flat case is more economical for daily use with multipurpose solutions. However, as the comparative data suggests, barrel cases used correctly with peroxide systems may offer a lower biofilm risk due to the enhanced cleaning action and complete lens immersion. The choice is less about saving solution and more about matching the case to the required disinfection system for optimal safety.

The Chemical Residue Risk of Washing Lens Cases in the Dishwasher

In an attempt to achieve a “deep clean,” some users resort to washing their contact lens cases in the dishwasher or boiling them in water. This is a dangerous and counterproductive practice. While the high heat seems like an effective sterilization method, it poses two significant risks: material degradation and chemical contamination. The polypropylene plastic used in lens cases is not designed to withstand such temperatures. Evidence from manufacturers indicates that plastic lens cases can deform at temperatures above 140°F (60°C), a threshold easily surpassed in most dishwashers.

This warping is not just a cosmetic issue. It compromises the seal of the case, leading to solution evaporation and incomplete disinfection. More importantly, it creates even more surface imperfections, expanding the number of micro-abrasion havens for bacteria to colonize. The second, more insidious risk is chemical residue. Dishwasher detergents are harsh and are not meant for medical devices that come into contact with your eyes. Residue can leach into the plastic and subsequently be released into your contact lens solution, leading to severe chemical irritation or allergic reactions in the eye.

There is no shortcut to proper hygiene. Boiling and dishwashing are unsafe “hacks” that do more harm than good. The only approved method for cleaning a contact lens case is the mechanical rubbing and rinsing protocol with a dedicated, fresh contact lens solution. This procedure is specifically designed to be effective without damaging the case material or introducing harmful chemicals. Substituting it with household cleaning methods turns a tool for hygiene into a potential source of both microbial and chemical injury.

Problem & Solution: Keeping Your Case Sterile While Camping

Maintaining contact lens hygiene in an outdoor environment like a campsite presents a unique set of challenges. The lack of a clean, controlled space and easy access to sterile supplies significantly increases the risk of contamination. Using unpurified water from a stream, wiping hands on clothing, or placing a case on an unclean surface can introduce a host of dangerous pathogens directly into your eyes. However, with proper preparation, you can create a portable sterile field and adhere to safe practices even when away from home.

The core principle is to isolate your lens care from the environment. This means never allowing your lenses, case, or solution bottle tips to touch any non-sterile surface. Before you leave, pack a dedicated “hygiene kit” containing travel-sized solution, a new contact lens case, antibacterial hand sanitizer (use it and let your hands air-dry completely before touching lenses), and clean, lint-free tissues or a small, clean microfiber cloth stored in a sealed bag. Daily disposable lenses are the safest option for camping, as they eliminate the need for cleaning and storage altogether.

If you must use reusable lenses, create a makeshift sterile field as depicted. Use a clean, flat surface and lay out your supplies without letting them touch the surrounding area. Perform all handling over this clean zone. After inserting your lenses, empty the old solution, rinse the case with fresh solution, wipe it dry, and store it in a sealed plastic bag to protect it from environmental contaminants throughout the day. This disciplined approach is essential to prevent a serious eye infection from ruining your trip.

Why Rinsing Cases With Tap Water Risks Acanthamoeba Infection?

The single most critical rule of contact lens care is to keep all forms of water away from your lenses and case. This includes tap water, shower water, lake water, and even bottled water. The reason for this strict prohibition is a dangerous, free-living amoeba called Acanthamoeba. This microorganism is commonly found in all water sources and soil. While harmless when ingested, it can cause a devastating, painful, and sight-threatening infection if it enters the eye: Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Acanthamoeba is incredibly resilient. It can exist in a tough, dormant cyst form that is highly resistant to temperature changes, drying, and even the chlorine levels found in treated tap water. When you rinse your case with tap water, you are potentially seeding it with these cysts. Once your contact lens and solution are added, the amoeba can revert to its active form, multiply, and attach to the lens. Wearing that lens then transfers the amoeba directly to your cornea, where it can cause infection.

It is a dangerous misconception that “clean” drinking water is safe for contact lenses. The concentration of disinfectants is simply not high enough to guarantee the elimination of these resilient organisms. As a leading health authority explains:

Even treated drinking water, bottled water or swimming pool water may not have a high enough chlorine concentration to kill Acanthamoeba.

– Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic Health Library

Only dedicated contact lens disinfecting solutions are formulated to effectively kill pathogens like Acanthamoeba. Using anything else, especially water, turns your lens case from a protective device into a contamination vector for one of the most severe forms of microbial keratitis.

Key Takeaways

- Your contact lens case is not sterile; micro-scratches create a breeding ground for drug-resistant biofilm.

- Proper daily care involves a “rub and rinse” method with solution, followed by air-drying face down in a clean area.

- The CDC-backed, evidence-based standard is to replace your case at least every three months to minimize infection risk.

Why You Must Discard Your Lenses Immediately Upon Seeing Redness?

Eye redness, pain, light sensitivity, or blurred vision while wearing contact lenses are not minor irritations; they are critical warning signs of a potential eye infection. The most serious of these is microbial keratitis, an infection of the cornea that can lead to permanent vision loss if not treated promptly. Attempting to “clean” the lens and re-insert it, or simply ignoring the symptoms, is a gamble with your sight. The moment you experience any of these symptoms, your lenses and your case should be considered contaminated.

From a statistical perspective, while the overall risk is low, the consequences are severe. Across the contact lens wearing population, the infection rate for microbial keratitis is approximately 4 to 6 per 10,000 wearers annually. The risk dramatically increases with poor hygiene compliance, such as overwearing lenses or failing to replace the case. When symptoms appear, the immediate priority is to remove the source of the infection and seek professional medical advice.

Do not attempt to self-diagnose. The contaminated lenses and case should be discarded immediately. Do not try to salvage them. Preserving them in a separate bag to bring to your eye doctor can sometimes help in identifying the causative organism, but they should never be worn again. Follow this emergency response protocol:

- Remove your contact lenses immediately upon noticing any redness, pain, discharge, or change in vision.

- Do not attempt to clean or reuse the lenses that were in your eyes when the symptoms started.

- Discard both the contaminated lenses and the contact lens case you are currently using.

- Contact your eye care professional without delay and explain your symptoms.

- Wear your backup eyeglasses until your doctor has examined you and cleared you to resume contact lens wear.

Acting decisively at the first sign of trouble is the most important factor in achieving a positive outcome and preventing long-term damage to your vision.

How to Recycle Daily Contact Lenses and Blister Packs Correctly?

Once you adopt a compliant case replacement schedule, the final piece of responsible lens wear is proper disposal. The accumulation of plastic from lenses, blister packs, and old cases contributes to environmental waste. Fortunately, awareness and programs have grown, making it easier to recycle these materials correctly. However, it requires a few specific steps, as these items cannot simply be tossed into a standard recycling bin.

Contact lenses themselves are too small to be sorted by standard municipal recycling facilities and will end up in landfill. The blister packs present another challenge: they are a composite of plastic (usually polypropylene #5) and a foil lid (aluminum). These materials must be separated to be recycled effectively. The foil must be completely removed from the plastic blister before placing the plastic part in your recycling bin, but only if your local program accepts #5 plastics.

The most effective method for recycling contact lens waste is through specialized take-back programs. Recognizing the compliance and environmental challenge, many eye care professionals and manufacturers have partnered with recycling companies to solve this problem. These programs provide a reliable way to ensure your contact lens waste is handled responsibly. The key takeaway from public health bodies like the CDC reinforces the foundation of this entire process: targeted prevention messages for wearers include replacing their contact lens case every 3 months. This hygiene mandate and environmental responsibility go hand in hand.

For the committed wearer, combining a strict, evidence-based hygiene protocol with a responsible recycling practice represents the gold standard of contact lens use. It protects both your personal health and the health of the environment.

Frequent Questions on Contact Lens Case Hygiene

Can contact lens cases be recycled?

Most contact lens cases are made from #5 PP (polypropylene) plastic and can be recycled where this plastic type is accepted. Check with your local recycling program first.

Should foil and plastic be separated from blister packs?

Yes, the aluminum foil must be separated from the plastic blister as they are different materials that contaminate recycling streams if mixed. Only the plastic part may be recyclable.

Are there manufacturer take-back programs?

Yes, programs like Bausch + Lomb’s ONE by ONE with TerraCycle accept contact lens waste, including lenses, blister packs, and foil, for specialized recycling. Check with your eye doctor for collection points.