Contrary to common belief, a -4.00 diopter prescription is not just a score for “bad vision”; it’s a precise physical measurement. It means your eye focuses light 25 centimeters in front of where it should, and the corrective lens required has a focal length of -25 cm to push that focus back onto your retina. This single number dictates everything from lens thickness to the difference between your glasses and contact lens prescriptions.

Receiving your new eye prescription can feel like decoding a secret message. You see the numbers—OD: -4.00, OS: -3.75—and you understand the gist: you’re nearsighted. You might even hear your prescription described as “moderate.” But what does that number, -4.00, actually signify? Most people stop at “it measures how strong my glasses are,” but this barely scratches the surface of the elegant physics at play.

The common understanding often conflates this measurement with visual acuity scores like 20/20, leading to a fundamental misunderstanding of how vision correction works. This article bypasses the platitudes. We will not just tell you that a negative number means you are nearsighted; we will explain *why* from a physics perspective. The key isn’t the “strength” of the lens, but its focal length—the precise distance at which it bends light to grant you clear vision.

By treating your prescription as a scientific instruction rather than a simple grade, you can unlock a deeper understanding of your own eyes. We will explore the direct relationship between diopters and your eye’s focal point, explain why glasses and contact lens prescriptions differ, and demystify how this measurement influences everything from the appearance of your eyes to your eligibility for surgical procedures. This is your guide to reading between the lines of your eye chart and truly owning your optical health.

To navigate this exploration of optical physics, the following guide breaks down each key concept. From the fundamental principles to practical applications, you’ll gain a comprehensive understanding of what your prescription truly means.

Summary: A Physicist’s Guide to Your Focal Distance

- Why Negative Diopters Shrink Eyes Appearance While Positive Ones Magnify?

- How to Adjust Diopters When Switching From Frames to Contacts?

- LASIK or ICL: Which Is Safer for Prescriptions Over -10 Diopters?

- The Mistake of Assuming -1.00 Diopter Equals 20/40 Vision

- Problem & Solution: Choosing Frames That Hide Thick Lenses for +5.00 Diopters

- How to Read Your Eye Chart Results Beyond the Bottom Line?

- Glasses Rx vs. Contact Rx: Why the Powers Are Never the Same?

- Astigmatism, Hyperopia, or Presbyopia: What Causes Your Blurry Text?

Why Negative Diopters Shrink Eyes Appearance While Positive Ones Magnify?

The apparent change in eye size behind lenses is a direct consequence of a lens’s primary function: bending light. A negative diopter lens, used to correct nearsightedness (myopia), is a concave lens. It is thinner in the center and thicker at the edges. This shape causes parallel light rays to diverge, or spread out. For your eye, this effectively pushes the focal point backward onto your retina, correcting your vision. As a side effect, this light divergence creates a “minification” effect, making your eyes appear smaller to an outside observer.

Conversely, a positive diopter lens for farsightedness (hyperopia) is a convex lens, thicker in the center. It converges light rays, which is why it has a magnifying effect on your eyes. The degree of this optical illusion is directly tied to the power of the lens. A -8.00 lens will cause more minification than a -2.00 lens.

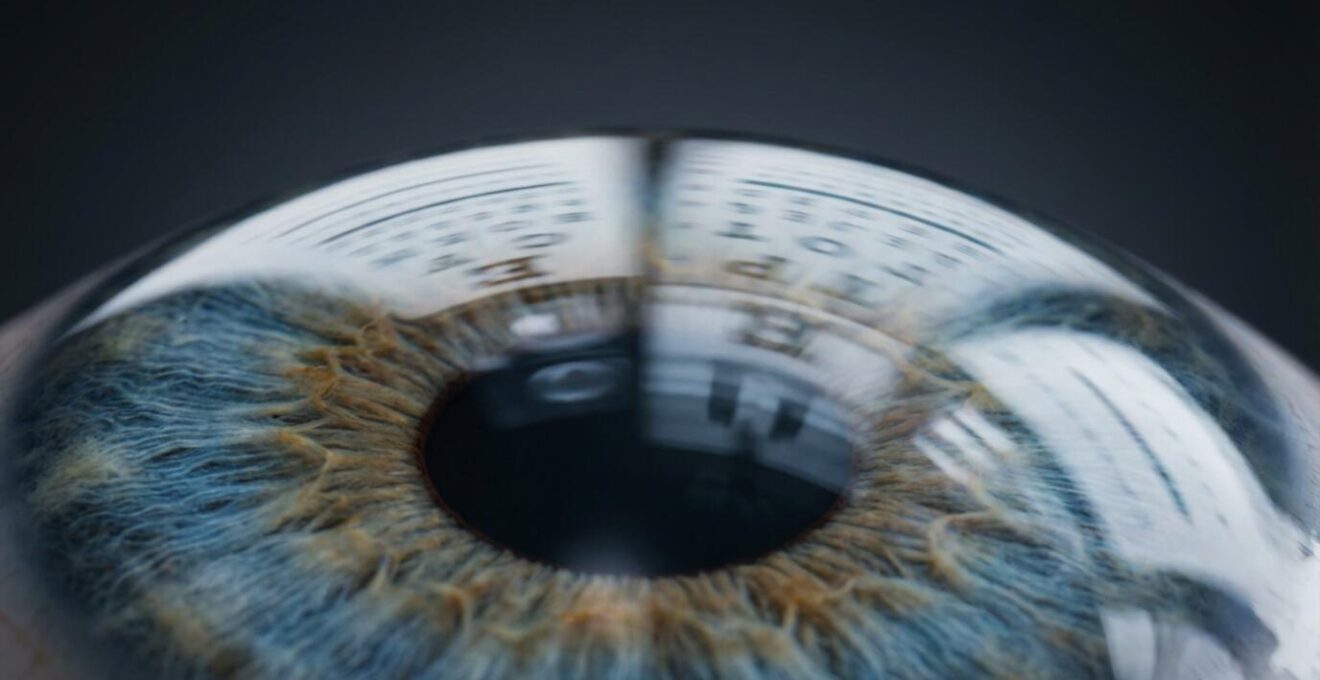

The physics behind this is rooted in the definition of a diopter. A lens’s power in diopters is the reciprocal of its focal length in meters (Power = 1/focal length). Therefore, a -4.00 D lens has a focal length of -0.25 meters (-25 cm). This relationship is fundamental, as optical principles state a 1 diopter lens brings objects into focus at a 1-meter distance. Understanding this principle is the first step to seeing a diopter not as a grade, but as a precise instruction for light refraction.

How to Adjust Diopters When Switching From Frames to Contacts?

If you’ve ever had prescriptions for both glasses and contact lenses, you’ve likely noticed the numbers aren’t identical, especially with stronger prescriptions. This isn’t an error; it’s a necessary adjustment based on a critical factor in optics: vertex distance. Vertex distance is the physical space between the back surface of an eyeglass lens and the front surface of the cornea. For a typical pair of glasses, this is about 12-14 millimeters.

This distance matters. An eyeglass lens is positioned to correct your vision from that 12mm gap. A contact lens, however, sits directly on the cornea, making the vertex distance zero. For low prescriptions, the 12mm difference is negligible. But as the diopter power increases, the effective power of the lens changes significantly with its distance from the eye. To provide the same optical correction, a contact lens for a myopic person must be slightly weaker (less negative) than its eyeglass counterpart.

The image above illustrates this spatial relationship. For a -4.00 D glasses prescription, the corresponding contact lens power is often around -3.75 D. The gap is small, but for a -10.00 D prescription, the contact lens might be as low as -8.75 D. This adjustment ensures the light is focused perfectly on the retina, regardless of whether the corrective lens is 12mm away or sitting right on your eye.

The following table, based on common clinical practice, illustrates these typical adjustments. It highlights why a simple one-to-one transfer of your glasses prescription to contacts is not only incorrect but would result in suboptimal vision.

| Glasses Prescription | Typical Contact Lens Adjustment | Vertex Distance Impact |

|---|---|---|

| -4.00 D | -3.75 D | 0.25 D reduction |

| -6.00 D | -5.50 D | 0.50 D reduction |

| -8.00 D | -7.00 D to -7.25 D | 0.75-1.00 D reduction |

| -10.00 D | -8.75 D to -9.00 D | 1.00-1.25 D reduction |

LASIK or ICL: Which Is Safer for Prescriptions Over -10 Diopters?

For individuals with high myopia, such as prescriptions exceeding -10.00 diopters, the conversation around permanent vision correction shifts. While LASIK is a well-known procedure, its suitability diminishes as refractive error increases. LASIK works by using a laser to reshape the cornea, effectively carving a corrective lens onto the eye’s surface. For a -10.00 D correction, this requires removing a significant amount of corneal tissue, which can compromise the structural integrity of the cornea and increase the risk of long-term complications like ectasia.

This is where Implantable Collamer Lenses (ICL) become a superior and often safer alternative. An ICL is not a subtractive procedure; it’s an additive one. It involves surgically placing a microscopic, biocompatible lens inside the eye, between the iris and the natural lens. This lens corrects the refractive error without removing any corneal tissue. As a result, it preserves the cornea’s natural shape and strength, making it a much safer option for high diopters. In fact, practice trends show that while ICL starts being recommended at -3.00 D, it is the preferred method for prescriptions over -10.00 D.

The effectiveness of ICL for this patient group is well-documented. In a US FDA follow-up study on highly myopic patients, a remarkable 83.8% of those with prescriptions over -10.00 D reported uncorrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better three years after the procedure. This high success rate, combined with the preservation of corneal tissue, makes it the gold standard. As one leading ophthalmologist, Dr. Thompson, stated in a 2024 EyeWorld article:

If I was a 30-year-old patient, and I was more than a 3 D myope, in addition to corneal refractive surgery, I’d be considering a phakic IOL.

– Dr. Thompson, EyeWorld 2024 Article on LASIK Decline

The Mistake of Assuming -1.00 Diopter Equals 20/40 Vision

One of the most pervasive misconceptions in optics is the attempt to create a direct, linear conversion between diopters and visual acuity scores like 20/40. While it’s tempting to use rules of thumb, the reality is that diopters measure refractive error, while acuity measures visual performance. They are related, but not interchangeable. A diopter is a unit of optical power needed for correction, whereas a 20/40 score means you can see at 20 feet what a person with “normal” vision can see at 40 feet.

The relationship between the two is highly individual. Factors like pupil size, lighting conditions, the health of your retina, and the presence of other optical aberrations all influence your final visual acuity. For this reason, two people with the exact same -4.00 D prescription might achieve different levels of best-corrected visual acuity. Furthermore, the uncorrected acuity can vary wildly. While some charts might suggest -1.00 D approximates 20/40, this correlation breaks down quickly. In fact, some optometry sources report the -4.00 to -6.00 D range can reflect uncorrected vision as poor as 20/400, depending on the individual.

Thinking in terms of focal distance provides a more accurate mental model. A -4.00 D prescription means your unaided eye’s far point of clear vision is just 25 centimeters (or about 10 inches) away. Anything beyond that point becomes progressively blurry. This physical reality is a more reliable measure than any estimated acuity score.

Your Action Plan: Demystifying Your Diopter Measurement

- Isolate the Concepts: Consciously separate “diopters” (lens power) from “visual acuity” (20/20 performance) in your mind.

- Embrace the Sign: Internalize that a negative (-) diopter number always indicates myopia (nearsightedness) and is a measure of light-diverging power.

- Focus on Focal Point: Calculate your far point by dividing 1 by your diopter value (e.g., 1 / 4.00 = 0.25 meters). This is your true zone of clear vision.

- Acknowledge Variability: Recognize that your Best Corrected Visual Acuity is unique to you and is not solely determined by your diopter number.

- Consider Context: Understand that your functional vision is also affected by external factors like pupil size and ambient lighting.

Problem & Solution: Choosing Frames That Hide Thick Lenses for +5.00 Diopters

While our focus has been on negative diopters, the principles of optical physics apply equally to positive diopters for farsightedness (hyperopia). A +5.00 D lens is a strong convex lens, meaning it’s thickest in the center and thinner at the edges. This creates a “Coke bottle” effect and significant magnification. The primary challenge is choosing a frame that minimizes this center thickness and weight for better aesthetics and comfort.

The solution lies in geometry. The thickness of a convex lens is a function of its power and its diameter. Therefore, the most effective strategy is to select a frame that is small and round. A smaller lens diameter directly translates to a thinner, lighter lens. Round shapes are particularly efficient because they keep the lens diameter consistent across all meridians, avoiding the extra width and thickness that come with wide rectangular or cat-eye styles.

Additionally, material choice is key. Full-rim plastic or acetate frames are excellent because the frame material itself can hide the edge thickness of the lens. Conversely, rimless or semi-rimless frames are generally not recommended as they leave the thick edges of the lens exposed. Pairing a small, round frame with a high-index lens material (which bends light more efficiently and can be made thinner) is the ultimate combination for a high plus prescription.

The following guide summarizes the suitability of different frame types for a high-power positive prescription. It demonstrates how strategic frame selection is not just a matter of fashion, but of applied physics.

| Frame Type | Suitability for +5.00 D | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Small Round Frames | Excellent | Minimizes center thickness |

| Large Rectangular | Poor | Increases lens thickness |

| Plastic Full-Rim | Good | Hides lens edges well |

| Rimless | Not Recommended | Exposes thick lens edges |

How to Read Your Eye Chart Results Beyond the Bottom Line?

A prescription chart is packed with information that goes far beyond the primary diopter number. Understanding these additional terms is key to grasping the full picture of your optical needs. The most common value you’ll see is SPH (Sphere), which represents the main spherical correction for myopia or hyperopia, like the -4.00 D we’ve been discussing. It’s called “spherical” because the correction is uniform across all meridians of the eye.

However, many people also have astigmatism, which means the eye is shaped more like a football than a sphere, causing light to focus on multiple points. This is corrected with two additional values: CYL (Cylinder) and Axis. The CYL value indicates the amount of dioptric power needed to correct the astigmatism, and it also has a plus or minus sign. The Axis is the orientation of that astigmatism, measured in degrees.

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the Axis is written as a number between 1 and 180. An axis of 180 degrees means the astigmatism is horizontal. Other terms you might see include “Plano” or “DS” (Diopter Sphere), which indicate that no correction is needed for astigmatism in that eye. Finally, for those over 40 with presbyopia, an “ADD” value indicates the additional magnifying power needed for near vision, typically for bifocal or progressive lenses.

Glasses Rx vs. Contact Rx: Why the Powers Are Never the Same?

We’ve established that glasses and contact lens prescriptions differ due to vertex distance, but the underlying physics deserves a closer look. Think of your eye and the corrective lens as a combined optical system. The goal of this system is to place the final focal point of light directly onto the retina. The power required from the lens to achieve this depends entirely on its position relative to the eye.

The phenomenon is governed by the principles of lens-effectivity. A minus lens (for myopia) becomes effectively stronger as it moves away from the eye and weaker as it moves closer. Therefore, to achieve the same corrective effect as a -4.00 D lens sitting 12mm away in a pair of glasses, a contact lens sitting directly on the eye must have less minus power (e.g., -3.75 D). For a plus lens (for hyperopia), the opposite is true: it becomes weaker as it moves away and stronger as it moves closer. A +4.00 D glasses wearer would need a stronger plus power in their contact lenses (e.g., +4.25 D).

This vertex distance adjustment becomes clinically significant for any prescription beyond +/- 4.00 D, which is why a separate contact lens fitting is non-negotiable. An optometrist uses precise formulas to calculate the correct power, ensuring that the light entering your eye is focused with perfect clarity, regardless of the lens’s location. This meticulous process underscores that vision correction is a science of precision, not approximation.

Key Takeaways

- A diopter is a physical unit of measurement: it is the reciprocal of the lens’s focal length in meters (e.g., -4.00 D = -0.25m focal length).

- Diopters (refractive error) and visual acuity (20/20 performance) are not the same; you cannot accurately convert one to the other.

- Vertex distance—the space between a glasses lens and the eye—is the physical reason why eyeglass and contact lens prescriptions are different.

Astigmatism, Hyperopia, or Presbyopia: What Causes Your Blurry Text?

While a -4.00 D prescription clearly defines a case of myopia, blurry vision can stem from several different refractive errors, each with a unique physical cause. Understanding the differences is essential for a complete picture of optical health. Myopia, as we’ve seen, occurs when the eye is slightly too long or the cornea is too curved, causing light from distant objects to focus in front of the retina. This makes distant objects blurry, while near objects remain clear.

Hyperopia (farsightedness) is the opposite. The eye is slightly too short or the cornea too flat, causing light to attempt to focus behind the retina. This forces the eye’s internal lens to work harder to pull the focus forward, especially for near tasks, leading to eye strain and blurry near vision. It is corrected with positive (+) diopter lenses.

Astigmatism is a different kind of error. It’s not about the length of the eye, but its shape. It occurs when the cornea is not perfectly spherical, but is shaped more like a football. This irregularity causes light to have multiple focal points instead of one, resulting in vision that is blurry or distorted at all distances, often with shadows or ghosting around letters. It is corrected with a CYL (cylinder) power in a specific axis.

Finally, presbyopia is an age-related condition that affects everyone, typically starting after age 40. It is a loss of flexibility in the eye’s natural lens, reducing its ability to change shape to focus on near objects. This is why people who have had perfect vision their whole lives suddenly need reading glasses. It is corrected with an “ADD” power, which is a positive diopter value added to a distance prescription for near tasks.

By moving beyond the simple number on your prescription and understanding the physics of focal length, vertex distance, and lens shape, you are no longer a passive recipient of a diagnosis. You are an informed partner in your own optical health, equipped to ask smarter questions and make better decisions about your vision. The next time you see “-4.00 D,” you won’t just see a number; you’ll see a precise, elegant solution to your eye’s unique way of seeing the world. For your next eye exam, consider asking your optometrist to explain your prescription in terms of focal distance to deepen your understanding even further.

Frequently Asked Questions on What Do -4.00 Diopters Actually Mean for Your Focal Distance?

What does SPH (Sphere) mean on my prescription?

SPH indicates that the correction for nearsightedness or farsightedness is spherical—equal in all meridians of the eye.

What does ‘DS’ or ‘Plano’ indicate?

‘Plano’ or ‘0.00’ means no spherical correction is needed in that eye, while ‘DS’ (Diopter Sphere) indicates there is no astigmatism.

How is the red-green balance test used?

This test uses the principle of chromatic aberration to fine-tune the spherical power of your prescription. Because red and green light focus at slightly different points, the test helps the optometrist determine if the lens power is too strong or too weak, ensuring the most accurate and comfortable correction.